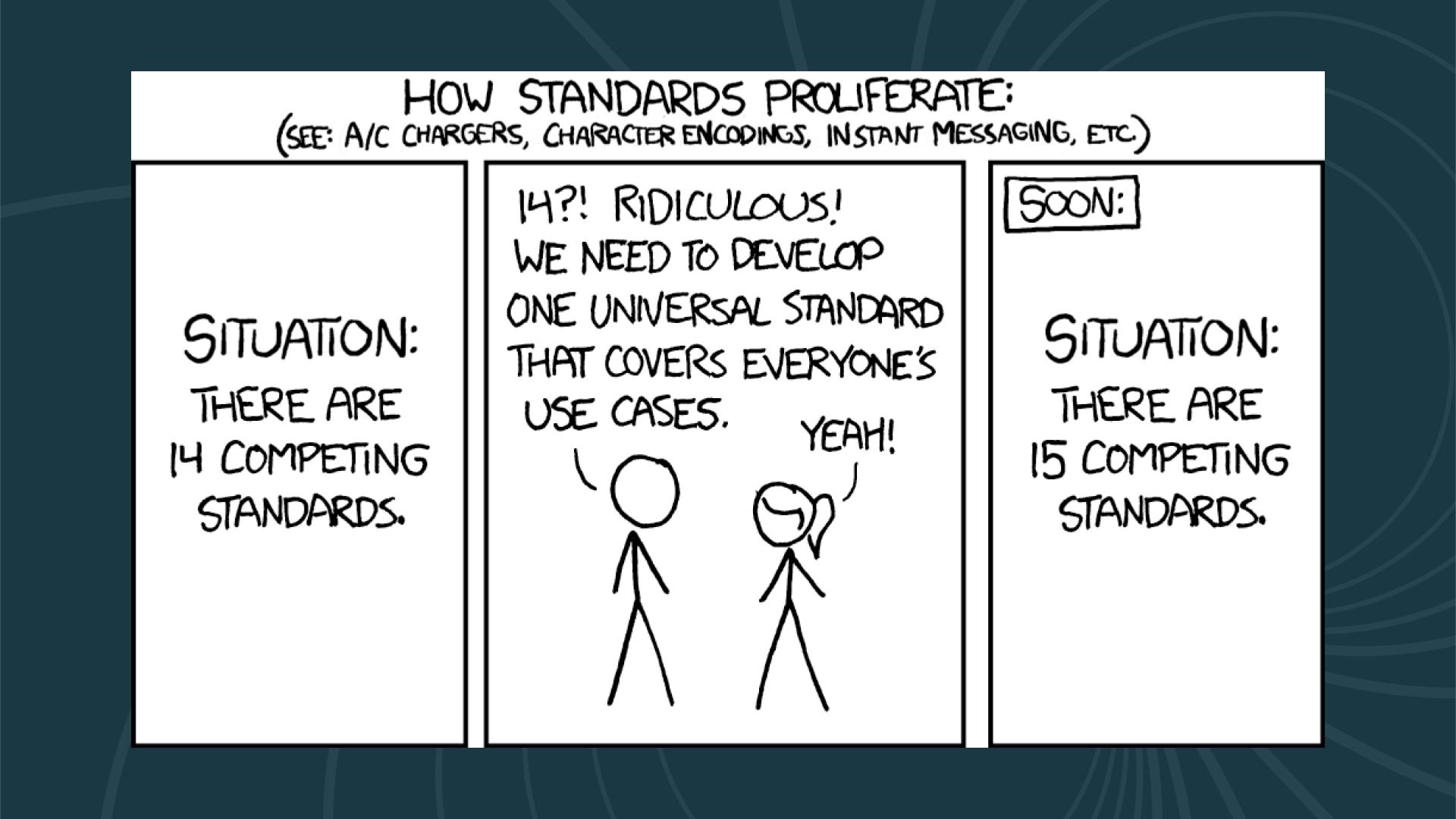

If you’ve ever felt overwhelmed by Python’s packaging ecosystem, you’re experiencing what the legendary XKCD comic #927 perfectly captured. The comic shows a familiar scenario: fourteen competing standards exist, someone declares “this is ridiculous, we need one universal standard,” and the final panel reveals there are now fifteen competing standards. For nearly two decades, Python packaging seemed trapped in exactly this recursive loop.

We transitioned from distutils to setuptools, introduced pip for installation and virtualenv for isolation, experimented with pipenv for lock files, embraced poetry for deterministic resolution, and explored pdm for standards compliance. Each tool promised to unify workflows around package installation, dependency resolution, and distribution. Each contributed valuable concepts like deterministic builds and standardized metadata, yet often created distinct, incompatible silos.

However, as we survey the landscape in 2026, something unexpected has happened. Rather than merely adding another configuration format to the pile, the industry has experienced genuine consolidation. This shift wasn’t driven initially by a committee decision but by a radical change in the underlying infrastructure of the tooling itself. The narrative of 2026 is defined by the tension between mature, pure-Python tools that stabilized the ecosystem and hyper-performant, Rust-based toolchains that have redefined developer expectations for speed and efficiency.

The Python packaging ecosystem has undergone dramatic transformation over the past few years, and 2026 marks a pivotal moment in how we think about dependency management, distribution, and development workflows. If you’re feeling overwhelmed by the proliferation of tools like uv, poetry, pip-compile, and others, you’re not alone. This guide will help you understand the modern Python packaging landscape, choose the right tools for your projects, and build secure, efficient workflows that scale from local development to production CI/CD pipelines.

The Evolution of Python Packaging

The journey from distutils to setuptools to pip to the modern tool ecosystem reflects Python’s growth from a scripting language to a first-class choice for everything from web applications to machine learning infrastructure. Each tool we’ll discuss emerged to solve specific problems that developers encountered in real-world projects. The introduction of PEP 517 and PEP 518 standardized build systems, the pyproject.toml file became the unified configuration format, and lock files evolved from a novel concept to an expected feature of modern workflows.

Understanding where we are today requires understanding where we came from, but more importantly, understanding that the fragmentation that followed wasn’t just chaos. While initially confusing, it has actually been healthy for the ecosystem. Competition has driven innovation, and in 2026, we’re reaping the benefits of that innovation with tools that are faster, more secure, and more reliable than ever before.

The Modern Python Packaging Stack: An Overview

Before diving into individual tools, it’s helpful to understand that Python packaging involves several distinct concerns. You need tools for dependency resolution, virtual environment management, lock file generation, package building, package distribution, and increasingly, package security. No single tool handles all of these equally well, which is why the landscape includes specialized tools for different parts of the workflow.

The key insight for 2026 is that you don’t need to choose just one tool. Most successful Python projects use a combination of tools, each excelling at its particular job. The art lies in understanding which combination works best for your specific needs, your team’s expertise, and your infrastructure constraints. In 2026, the fragmentation is no longer about how to define a package—thanks to the widespread adoption of pyproject.toml and PEP 621—but about which engine drives the development lifecycle.

uv: The Rust Revolution and Performance as a Feature

Released by Astral in 2024, uv has rapidly become one of the most transformative developments in Python packaging. Written in Rust, uv brings unprecedented speed to Python package installation and resolution, but more importantly, it represents a philosophical shift in how we think about developer tooling. If the early 2020s were defined by the standardization of pyproject.toml, the mid-2020s have been defined by what some call the “Rustification” of Python infrastructure. Where pip might take minutes to resolve complex dependency trees, uv often completes the same work in seconds. The performance improvements are not incremental refinements but rather represent a fundamental rethinking of how package installation should work.

uv’s philosophy centers on speed without sacrificing correctness, and understanding the technical foundation of this speed helps explain why it has become so dominant. It implements the same resolution logic as pip but does so with aggressive caching, parallel downloads, and highly optimized algorithms. The Rust implementation allows uv to skip Python’s interpreter overhead entirely and execute dependency resolution and file operations at native speed. More importantly, uv overlaps network operations, decompression, and disk writes in a parallel pipeline, whereas pip handles each step serially. This architectural difference means that while pip waits for one operation to complete before starting the next, uv keeps all available CPU cores busy with concurrent download, extract, and install tasks.

The technical innovations that make uv fast deserve detailed explanation because they represent genuine advances in package management technology. On supported filesystems like APFS on macOS or Btrfs on Linux, uv uses Copy-on-Write semantics and hard links to avoid actually copying package files during installation. Instead, it maintains a global cache of all packages you’ve ever installed and creates hard links from your virtual environment to that cache. This means that if you have requests version 2.31.0 in ten different projects, the actual file data exists only once on your disk, and each project’s virtual environment simply links to that shared copy. When you create a new environment and install cached packages, the installation happens near-instantly because no actual file copying occurs, just metadata operations to create the links.

The performance differential has shifted uv from a niche experiment to the default choice for high-velocity engineering teams. The speed is not merely a convenience but fundamentally alters developer behavior. When an environment can be recreated in milliseconds rather than minutes, developers are more likely to test in clean environments, reducing the “it works on my machine” class of bugs that plague software development. Let’s look at real-world benchmark data to understand the magnitude of improvement:

| Operation | pip + venv | poetry | uv | Speedup Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold Install (Fresh Cache) | 45s | 58s | 1.2s | ~35x |

| Warm Install (Cached) | 12s | 15s | 0.1s | ~100x |

| Lock File Resolution (Complex) | 180s | 210s | 2.5s | ~80x |

| Container Build Time | 3.5m | 4.2m | 20s | ~10x |

| Monorepo Sync (50+ packages) | N/A | 5m+ | 15s | ~20x |

The “Cold Install” metric is particularly relevant for CI/CD pipelines where caching strategies may not always persist between builds. The “Warm Install” metric demonstrates uv’s aggressive use of filesystem optimizations, allowing it to effectively “install” packages near-instantly by linking to a global cache rather than copying files. These aren’t benchmarks from idealized test scenarios but rather represent real-world performance across standard development tasks in 2026.

Beyond raw speed, uv introduced a unified project management philosophy that disrupted the fragmented toolchain that existed before 2024. Prior to uv, a sophisticated Python developer’s machine was a patchwork of tools: pyenv to manage Python versions, poetry or pipenv to manage project dependencies and lock files, pipx to run global Python CLIs like black or ruff in isolated environments, and virtualenv or the venv module for manual environment creation. In 2026, uv handles this entire lifecycle, reducing the cognitive load and setup time for new contributors to Python projects.

uv manages Python installations directly through its own managed registry of Python builds, effectively obsoleting pyenv for many users. If a project requires Python 3.13 and it’s not present on the system, uv downloads a standalone build, verifies its checksum, and uses it to bootstrap the virtual environment without any user intervention. One of uv’s most powerful features is the uvx command (or uv tool run), which allows for execution of Python tools in ephemeral, disposable environments. This replaces pipx for many use cases while being substantially faster. Running a specific version of a linter or security scanner no longer requires a global install; the tool runs in an ephemeral environment and the dependencies are cached for future use.

# Run a tool without installing it globally - ephemeral execution

uvx pycowsay "Hello from the ephemeral void"

# Initialize a new project with a specific Python version

# This downloads Python 3.12 if not present and creates a virtual environment

uv init my-analytics-app --python 3.12

cd my-analytics-app

# Add dependencies (updates pyproject.toml and uv.lock)

# The resolution engine runs in parallel, utilizing all available CPU cores

uv add pandas requests "fastapi>=0.110"

uv add --dev ruff pytest

# Synchronize the environment to match the lockfile exactly

# This removes extraneous packages not in the lockfile

uv sync

# Run commands within the project's environment

# No need to manually activate (source .venv/bin/activate)

uv run pytest

# Run a one-off script with inline metadata (PEP 723)

# Installs dependencies into temporary cache before execution

uv run --script scripts/data_migration.py

However, the “monolithization” of packaging via uv has faced valid criticism that deserves acknowledgment. The primary concern in 2026 revolves around what some call the “bus factor” risk. pip and poetry are written in Python, which means that if they break, any Python developer can debug the stack trace, understand the problem, patch the code, and potentially contribute a fix upstream. uv is written in Rust. While this grants the performance we’ve discussed, it creates a significant barrier to contribution for the vast majority of the community it serves. If a critical bug were discovered in uv’s resolver tomorrow, the number of people capable of fixing it is orders of magnitude smaller than for pip. This risk is mitigated by Astral’s corporate backing and their track record with projects like ruff, but it remains a point of contention for open-source purists who value community maintainability.

Furthermore, architectural purists argue that uv’s aggressive bundling of features violates the Unix philosophy of small, composable tools. By combining the functionality of pip, pip-tools, pipx, poetry, pyenv, twine, and virtualenv into a single binary, uv creates a monolithic system where failure in one component could theoretically affect all others. However, the overwhelming market sentiment in 2026 suggests that developers generally prefer the convenience of a unified, “batteries-included” toolchain over modular purity, especially when that convenience comes with dramatic performance improvements.

For developers working on large projects with hundreds of dependencies, the time savings are transformative. Consider a typical machine learning requirements file containing packages like tensorflow, torch, scikit-learn, pandas, numpy, and matplotlib. On a local development machine with multiple cores, installing these dependencies with pip might take one minute and forty-seven seconds, while uv completes the same installation in just thirty-five seconds. That represents a sixty-six percent improvement in wall clock time, and more importantly, it means the difference between staying in flow and context-switching to other tasks while waiting for installations to complete.

The tool excels particularly in continuous integration environments, but there’s an important caveat that becomes clear when you understand the source of uv’s speed advantage. Much of uv’s performance gain comes from full CPU utilization through concurrent operations. On a modern development machine with four, eight, or more cores, this parallelism delivers dramatic improvements. However, CI environments often run on virtual machines with limited CPU allocation. A typical GitHub Actions runner or AWS CodeBuild instance might have only one or two virtual CPUs assigned to it.

To understand the real-world impact, consider benchmark data from testing both pip and uv in Docker containers with CPU limits that simulate CI environments. When installing the same machine learning dependencies with a single CPU core allocated (using Docker’s --cpus 1 flag), pip takes about one minute and forty-three seconds, while uv completes the installation in one minute and thirty-five seconds. That’s still an improvement of about eight seconds, but it’s nowhere near the seventy-two second improvement seen on unrestricted hardware. The benefit shrinks because you’ve removed the primary advantage that makes uv faster: its ability to saturate multiple CPU cores with parallel operations.

This doesn’t mean uv isn’t valuable in CI environments. Eight seconds saved per build still compounds over hundreds or thousands of builds. However, it does mean that teams expecting to replicate their local development speed improvements in CI may be disappointed if they’re using standard, minimal CI runner configurations. The solution, which we’ll discuss more in the section on private package repositories, is to address the other bottleneck: network latency and PyPI’s response times. Even with a single CPU core, uv can deliver substantial improvements when paired with a faster package index that reduces the time spent waiting for package metadata and downloads.

The ideal use case for uv is as a comprehensive solution for modern projects that primarily pull from PyPI or standard private repositories. It works beautifully with requirements.txt files, natively generates lock files, and provides a unified developer experience from project initialization through deployment. For teams using private package repositories like RepoForge.io, uv’s speed benefits extend to internal packages as well, making development iteration substantially faster. The combination of uv’s parallel execution with a low-latency private repository can deliver the same dramatic improvements in CI that you experience locally, even on CPU-constrained runners.

poetry: The All-in-One Developer Experience

poetry represents a different philosophy from uv. Rather than focusing on one piece of the packaging puzzle, poetry aims to be a comprehensive solution for Python project management. It handles dependency management, virtual environments, package building, and publishing all through a single, cohesive interface. For developers who appreciate opinionated tools that make decisions for you, poetry offers an attractive workflow that feels modern and well-integrated from end to end.

The centerpiece of poetry is the pyproject.toml file, which serves as the single source of truth for your project. This file defines your dependencies, build system, metadata, and tool configuration in a standardized format that’s becoming increasingly common across the Python ecosystem. poetry then generates a poetry.lock file that pins exact versions of all dependencies and their transitive dependencies, ensuring that everyone working on the project has identical environments. This lock file approach eliminates the classic “works on my machine” problem by guaranteeing reproducible builds across development, staging, and production environments.

For developers coming from Node.js and npm, poetry feels familiar and intuitive. The workflow of adding dependencies, installing packages, and building distributions maps naturally to npm’s commands, but with Python-specific enhancements. This familiarity has made poetry popular among developers who work across multiple languages and appreciate consistent workflows regardless of the underlying ecosystem.

Let’s look at how you actually use poetry in practice. When starting a new project, poetry creates the project structure and configuration for you with sensible defaults. You can then add dependencies interactively, and poetry handles version resolution and lock file updates automatically.

# Create a new poetry project

poetry new my-awesome-project

cd my-awesome-project

# Add a dependency - poetry resolves versions and updates the lock file

poetry add requests

# Add a development dependency

poetry add --group dev pytest

# Install all dependencies from the lock file

poetry install

# Run a command within the virtual environment

poetry run python my_script.py

# Build your package for distribution

poetry build

# Publish to PyPI or a private repository

poetry publish --repository my-private-repo

poetry’s dependency resolver is sophisticated and generally produces correct results even with complex dependency graphs. It understands semantic versioning, can navigate tricky dependency constraints, and provides clear error messages when conflicts arise. When you add a new package, poetry figures out if it’s compatible with your existing dependencies and updates your lock file accordingly. If there’s a conflict, poetry explains what’s incompatible and why, helping you understand the constraint problem rather than just failing mysteriously.

The all-in-one nature of poetry is both its greatest strength and a potential limitation depending on your needs. If you’re starting a new project and want to get up and running quickly with modern Python packaging practices, poetry provides an excellent experience. A single tool handles everything you need, from project initialization through dependency management to package publishing. The learning curve is manageable because you’re learning one tool’s paradigm rather than juggling multiple tools with different interfaces and assumptions.

However, if you have specific requirements for parts of your workflow, poetry’s integrated approach can feel constraining. Perhaps you need pip-compile’s features for generating constraints files for complex multi-environment setups, or you prefer a different virtual environment manager, or you want to use a specific build backend that poetry doesn’t support. In these cases, poetry’s opinion about how things should work might conflict with your requirements. The tool makes strong assumptions about workflow, and while those assumptions work well for many projects, they’re not universally applicable.

Performance is another consideration worth understanding. While poetry has improved significantly over the years through optimization work and better dependency resolution algorithms, it’s still slower than specialized tools like uv for package installation. The resolver has to do more work because it’s providing additional features like semantic version understanding and comprehensive conflict detection. For many projects, especially smaller to medium-sized applications, this trade-off makes perfect sense. You sacrifice some raw installation speed in exchange for a more curated, integrated experience that catches problems early and provides better error messages when things go wrong.

poetry shines particularly in application development rather than library development. If you’re building a web application with Django or FastAPI, a data pipeline with Airflow, or an internal tool for your organization, poetry provides an excellent end-to-end workflow. The lock file ensures your production deployments match your development environment exactly. The integrated virtual environment management means you don’t need to remember to activate environments manually. The build and publish commands are right there when you need them, using the same tool and configuration you’ve been using throughout development.

pip-compile and pip-tools: The Pragmatic Middle Ground

pip-tools, and specifically its pip-compile command, represents a pragmatic approach to dependency management that appeals to developers who want reproducible builds without adopting an entirely new workflow. Rather than replacing your entire packaging stack, pip-tools augments the standard pip and requirements.txt approach with lock file functionality. This incremental improvement strategy makes pip-tools particularly attractive for teams with existing projects who want to adopt modern practices without a complete rewrite of their build and deployment pipelines.

The core concept is simple but powerful, and understanding it helps clarify why pip-tools has remained popular even as newer, flashier tools have emerged. You maintain a requirements.in file with your direct dependencies, potentially with loose version constraints that express what you actually care about. You then run pip-compile to generate a requirements.txt file with all dependencies pinned to specific versions, including all transitive dependencies that your direct dependencies rely on. This gives you reproducible environments while keeping your dependency declarations clean and maintainable. Your requirements.in file says “I need Django and Redis,” while your requirements.txt file says “I need Django 4.2.7, asgiref 3.7.2, sqlparse 0.4.4, redis 5.0.1, and async-timeout 4.0.3,” capturing the entire dependency tree.

This approach has several advantages that become clear when you start using it in real projects. First, it’s minimal and focused. pip-tools does one thing well rather than trying to be everything to everyone. This focused scope means it’s easy to understand, easy to debug when problems occur, and easy to integrate into existing workflows. Second, it integrates seamlessly with existing Python tooling because you’re still using pip for installation. Any workflow or tool that works with pip works with pip-tools. Your deployment scripts don’t need to change. Your CI configuration doesn’t need to change. You simply add one compilation step that generates the lock file from your input file.

Third, pip-tools is transparent in a way that some integrated tools are not. The generated requirements.txt file is human-readable, making it easy to understand exactly what’s installed and why. If you’re curious about where a particular package came from, you can trace it back through the comments that pip-compile adds to the requirements.txt file. These comments show which top-level requirement pulled in each transitive dependency, creating an audit trail that helps you understand your dependency graph.

Here’s how you use pip-compile in practice. The workflow centers around maintaining .in files for your dependencies and compiling them into .txt files that get checked into version control and used for actual installation.

# Install pip-tools

pip install pip-tools

# Create a requirements.in file with your direct dependencies

echo "django>=4.2" > requirements.in

echo "redis>=5.0" >> requirements.in

echo "celery>=5.3" >> requirements.in

# Compile into a fully pinned requirements.txt

pip-compile requirements.in

# Install the pinned dependencies

pip install -r requirements.txt

# Update dependencies to latest compatible versions

pip-compile --upgrade requirements.in

# Update just one dependency

pip-compile --upgrade-package django requirements.in

pip-compile excels at generating different requirements files for different purposes, and this capability becomes important as your project grows in complexity. You might have requirements.in for production dependencies, dev-requirements.in for development tools like pytest and black, and docs-requirements.in for documentation generation with Sphinx. You can use constraints files to ensure consistency across these different environments, guaranteeing that when a transitive dependency appears in multiple compiled files, it has the same version everywhere. This flexibility makes pip-tools popular in organizations with complex deployment requirements where different services or environments need different but overlapping sets of dependencies.

The tool also integrates naturally with private package repositories, which becomes increasingly important as your organization grows and you need to distribute internal packages. If you’re using RepoForge.io to host internal packages, pip-compile respects your pip configuration and generates lock files that include your private packages exactly like PyPI packages. The workflow remains consistent whether you’re pulling from public or private sources. You can even use pip-compile’s --index-url and --extra-index-url options to specify your private repository explicitly.

# Compile with a private repository

pip-compile --index-url https://api.repoforge.io/your-hash/ requirements.in

# Or use extra index to search both PyPI and your private repo

pip-compile --extra-index-url https://api.repoforge.io/your-hash/ requirements.in

One limitation of pip-tools that’s worth understanding is that it doesn’t handle virtual environment management. You need to use venv, virtualenv, or another environment manager separately. For some developers, this separation is actually preferable because it keeps concerns separate and lets you use your preferred environment management approach. For others, the integrated experience of poetry or hatch is more appealing. Neither approach is inherently better, but understanding the trade-off helps you choose what fits your workflow.

pip-compile also doesn’t have a concept of semantic versioning resolution the way poetry does. It uses pip’s resolver under the hood, which means it gets the same correct results but doesn’t provide the same level of feedback about why certain versions were chosen or what constraints are in conflict. When a resolution fails, you get pip’s error message, which can sometimes be cryptic for complex dependency graphs. However, for most real-world projects, this is rarely a problem, and the simplicity of pip-tools’ approach outweighs the occasional difficulty in understanding resolution conflicts.

Package Distribution and Security: Why You Need Private Repositories

Understanding the tools that install and manage packages is only half the story. The other critical piece is understanding how packages get distributed and why the default approach of publishing everything to public PyPI creates security risks that many organizations don’t fully appreciate. Package distribution is where abstract concerns about dependency management become concrete security and business continuity issues that can affect your entire organization.

The public Python Package Index has served the Python community extraordinarily well for many years. It’s free, it’s fast enough for most purposes, and it has excellent uptime. However, PyPI’s openness, which is one of its greatest strengths for the community, also creates vulnerabilities that become problematic as your projects move from hobby experiments to production systems that handle real user data and business-critical operations.

The most insidious security threat facing Python developers today is typosquatting, sometimes called dependency confusion attacks. The attack works because of a simple human vulnerability: developers make typos. An attacker registers a package with a name that’s one character different from a popular package, like “requestes” instead of “requests” or “beatifulsoup4” instead of “beautifulsoup4”. They might also register “numpy-utils” when the real package is just “numpy”, exploiting developers’ assumptions about how packages are named. The malicious package often includes the real package as a dependency, so the installation seems to work correctly. However, it also includes code that exfiltrates environment variables, steals AWS credentials, opens reverse shells, or installs cryptocurrency miners. By the time you notice something is wrong, the damage is done.

What makes typosquatting particularly dangerous is that it can affect you even if you never make a typo yourself. If one of your dependencies gets typosquatted, and you install it through a transitive dependency chain, you might pull in the malicious package without ever having typed its name. Your requirements file says “install framework-x”, framework-x depends on “utility-y”, but utility-y’s maintainer made a typo in their setup.py and accidentally specified “requestes” instead of “requests”. Now your entire infrastructure is potentially compromised because of someone else’s typo three levels deep in your dependency tree.

The scale of this problem is sobering. Security researchers regularly find typosquatted packages on PyPI, and while the PyPI team removes them when discovered, there’s always a window of time between when a malicious package is uploaded and when it’s detected and removed. During that window, thousands of developers might install it. The attacks are becoming more sophisticated too. Early typosquatting attempts were crude and easy to detect, but modern attacks include actual functionality that makes them harder to identify as malicious. Some attackers even contribute legitimate features to make their packages seem valuable while hiding malicious code in infrequently executed code paths.

Even beyond intentional attacks, public PyPI creates operational risks. A package you depend on might be removed by its author, either intentionally or because of a dispute with PyPI’s moderation team. A maintainer might abandon a project, and the package namespace might get taken over by someone with different intentions. The package might be updated in a way that breaks your application, and if you don’t have version pinning in place, your next deployment could suddenly fail. These scenarios, while less dramatic than security attacks, can still cause significant business disruption.

The solution to these problems is to use private package repositories for your internal code and, increasingly, for all your dependencies including those originally from PyPI. A private repository gives you complete control over what packages are available to your developers and what versions of those packages they can install. This control enables several important security practices that are difficult or impossible with public PyPI alone.

First, you can curate your allowed packages. Rather than giving developers access to all two hundred thousand packages on PyPI, many of which are abandonware or outright malicious, you explicitly choose which packages your organization trusts. This curation process might seem like overhead, but it’s far less overhead than responding to a security incident caused by a typosquatted package. When a developer needs a new package, they request it, your security team reviews it, and once approved, it goes into your private repository where all developers can access it. This creates a firewall between the Wild West of public PyPI and your production systems.

Second, you can scan packages for vulnerabilities before they reach your developers. When you pull a package from PyPI into your private repository, you can run automated security scans that check for known CVEs in the code, inspect the package contents for suspicious patterns, and verify that the package actually does what it claims to do. If a vulnerability is discovered in a package you’re already using, you can block the vulnerable versions in your private repository, preventing new projects from using them while you plan migration strategies for existing uses.

Third, you can ensure business continuity even if PyPI has issues. If PyPI goes down, has performance problems, or starts rate-limiting your CI pipeline because of heavy use, your private repository continues serving packages normally. You’ve essentially created a local cache of all the packages you need, and that cache is under your control. This independence becomes particularly important during incident response. When you’re trying to roll back to a working version of your application because of a production issue, the last thing you want is to discover that PyPI is slow or a critical package has been deleted.

Fourth, and perhaps most importantly, a private repository gives you a secure place to host internal packages that shouldn’t be public. Every organization eventually builds shared libraries, internal tools, or business logic that needs to be packaged and distributed across multiple projects. Publishing these to public PyPI is obviously not an option because it would expose your internal code to the world. A private repository gives you a way to distribute internal packages using the same workflows and tools you use for public packages. Your developers install internal packages the same way they install public ones, and your CI systems don’t need special cases for internal versus external dependencies.

This is precisely where RepoForge.io becomes an essential part of your Python infrastructure. Rather than setting up and maintaining your own package index server, with all the associated infrastructure complexity, security patching, backup management, and operational overhead that entails, RepoForge provides a hosted private repository that works seamlessly with all the tools we’ve discussed. You get the security benefits of a private repository without the operational burden of running one yourself.

The workflow is straightforward and designed to feel natural to anyone familiar with Python packaging. You configure your development machines and CI systems to use your RepoForge URL as a package index. This can be your only index, meaning all packages must go through RepoForge first, or it can be an additional index that supplements PyPI. When you want to use a public package, you publish it to your RepoForge repository once, either manually or through an automated approval process. From that point forward, all your developers and CI systems install that package from RepoForge. When you create internal packages, you publish them to RepoForge using the same tools you’d use for PyPI, like twine or poetry’s publish command.

# Configure pip to use RepoForge

pip config set global.index-url https://api.repoforge.io/your-hash/

# Or use it alongside PyPI

pip config set global.extra-index-url https://api.repoforge.io/your-hash/

# Install packages normally - they come from RepoForge

pip install requests django

# Publish your internal package to RepoForge

twine upload --repository-url https://api.repoforge.io/your-hash/ dist/*

The performance characteristics of RepoForge matter as much as its security benefits, especially when we consider the CI/CD discussion from earlier. Remember how uv’s performance advantage diminishes in CPU-constrained CI environments because its parallelism can’t compensate for single-core limitations? The other major bottleneck in those environments is network latency and package index response time. PyPI is fast but not instantaneous, and when you’re installing dozens of packages, those individual latencies compound into significant total installation time.

RepoForge addresses this by providing extremely low-latency API responses and aggressive CDN caching. When your CI runner requests package metadata or downloads a wheel file, RepoForge serves it from edge locations close to your infrastructure, reducing round-trip times dramatically. In benchmarked testing with that same machine learning requirements file we discussed earlier, installing from RepoForge instead of PyPI in a single-CPU Docker container reduced installation time from one minute forty-three seconds to one minute twenty-seven seconds, even when using standard pip. That’s a sixteen-second improvement just from reducing network latency. When you combine RepoForge with uv, installation time drops to forty-eight seconds, representing a fifty-five percent improvement over the baseline pip-from-PyPI approach. These improvements compound across every CI build, every developer environment setup, and every deployment, ultimately translating to faster development cycles, lower CI costs, and developers spending less time waiting for dependencies to install.

The security and performance benefits we’ve discussed make private repositories like RepoForge essential infrastructure for professional Python development. The question is not whether you’ll eventually need a private repository, but rather how much pain you’ll endure from security incidents, slow CI pipelines, and fragile PyPI dependencies before you implement one. Starting with private repositories early in your project’s lifecycle establishes secure patterns from the beginning and avoids the difficult migration process of retrofitting security into an existing system built around direct PyPI access.

pip: The Foundational Standard

Despite the proliferation of new tools with impressive performance characteristics and integrated workflows, pip remains the foundation of Python packaging. Understanding pip is essential because nearly every other tool in the ecosystem either builds on pip, wraps pip, or at minimum needs to interoperate with pip’s conventions and behaviors. pip is what actually installs packages at the lowest level, even when you’re using higher-level tools that invoke it behind the scenes and hide that implementation detail from you.

pip’s role in 2026 has evolved from being the primary tool that developers interact with daily to being more of a foundational layer that provides core functionality for the rest of the ecosystem. It’s less common to use pip directly for dependency management in production applications where lock files and reproducible builds are essential. Instead, pip serves as the installation engine that other tools leverage when they need to actually put packages into Python environments. However, for quick experiments, small scripts, exploratory data analysis, or system-level Python installations where you’re just getting something working quickly without worrying about reproducibility, pip remains perfectly adequate and familiar.

The pip resolver, which was completely rewritten and released in 2020 after years of development work, provides correct dependency resolution according to Python’s packaging standards. While it’s slower than newer tools like uv that optimize for speed through parallelism and compiled code, pip is reliable and handles edge cases well because of its maturity and conservative implementation. For projects with complex dependency graphs, unusual version constraints, or packages that do strange things during installation, pip’s conservative approach sometimes produces better results than faster alternatives that optimize for the common case but might stumble on edge cases.

Here’s how you use pip for basic package management, which establishes the baseline that other tools improve upon:

# Install a package

pip install requests

# Install with version constraints

pip install 'django>=4.0,<5.0'

# Install from a requirements file

pip install -r requirements.txt

# Install from a specific index

pip install --index-url https://api.repoforge.io/your-hash/ mypackage

# Upgrade a package to the latest version

pip install --upgrade requests

# Uninstall a package

pip uninstall requests

# Show installed packages

pip list

# Show package information

pip show django

pip also serves as the reference implementation for Python packaging standards, which gives it a special status in the ecosystem beyond just being another tool. When questions arise about how something should work, how a particular PEP should be interpreted, or how packages should behave in edge cases, pip’s behavior often defines the answer. This makes pip crucial for package authors who want to ensure their packages work correctly across different tools and environments. If your package works with pip, it will almost certainly work with everything else. The reverse is not always true.

setuptools: The Build System Foundation

setuptools holds a special and historically important place in Python packaging. For many years, it was the standard way to define how Python packages should be built and distributed. While new build systems have emerged in recent years offering different approaches and capabilities, setuptools remains widely used and deeply integrated into the ecosystem. Understanding setuptools helps you understand the foundations that modern tools are built upon, and it remains directly relevant if you’re maintaining existing packages or need fine-grained control over the build process.

The key thing to understand about setuptools in 2026 is that it’s primarily a build backend rather than a complete packaging solution that handles every aspect of your workflow. When you define your project in pyproject.toml with build-system.requires including setuptools, you’re specifying that setuptools should handle the process of turning your source code into distributable wheels and source distributions that can be uploaded to package indexes. This build backend role is distinct from dependency management, installation, or environment management, which are handled by other tools in your stack.

setuptools is mature in the best sense of that word. It’s been around long enough to have encountered and solved many edge cases that newer build systems might miss or handle incorrectly. If you’re working with C extensions that need to be compiled, with data files that need to be included in your distribution, with namespace packages that have tricky import requirements, or with complex package structures that don’t follow simple conventions, setuptools has likely encountered your problem before and provides mechanisms to handle it. The documentation is extensive if sometimes dense, and the community knowledge around setuptools is vast because of its long history.

However, setuptools can be verbose and sometimes confusing, particularly if you’re looking at older projects that use setup.py files. The setup.py approach, while still supported for backwards compatibility, has largely given way to declarative configuration in pyproject.toml or setup.cfg files. This shift toward declarative configuration has made setuptools more approachable for new projects, but the legacy of setup.py means there’s a lot of outdated information scattered across the internet that can confuse developers trying to learn modern setuptools practices.

Here’s how setuptools is typically used in modern Python projects through pyproject.toml configuration:

# pyproject.toml - Modern setuptools configuration

[build-system]

requires = ["setuptools>=61.0"]

build-backend = "setuptools.build_meta"

[project]

name = "mypackage"

version = "1.0.0"

description = "A sample Python package"

authors = [{name = "Your Name", email = "you@example.com"}]

dependencies = [

"requests>=2.28.0",

"click>=8.0.0"

]

[project.optional-dependencies]

dev = ["pytest>=7.0", "black>=23.0"]

# Build your package using setuptools

python -m build

# This creates wheel and source distributions in dist/

# dist/mypackage-1.0.0-py3-none-any.whl

# dist/mypackage-1.0.0.tar.gz

For library authors and package maintainers, setuptools remains a solid choice when you need a mature, well-understood build backend. It’s compatible with every tool in the ecosystem, produces standard-compliant packages that work everywhere, and gives you fine-grained control over the build process when you need it. For application developers who mostly consume packages rather than publishing them, you may never interact with setuptools directly, as your dependency management tool handles any setuptools interactions behind the scenes.

twine: The Secure Distribution Tool

twine serves a focused and important purpose in the Python packaging ecosystem. It uploads packages to package indexes like PyPI or private repositories like RepoForge.io. While this might seem like a small role compared to the comprehensive tools we’ve discussed that handle multiple aspects of packaging, twine does its job well and securely, which matters enormously when you’re publishing code that other developers will depend on or that represents your organization’s intellectual property.

The primary advantage of twine over alternative approaches is that it uses HTTPS exclusively for uploads and validates TLS certificates, ensuring that your package uploads are secure and can’t be intercepted or tampered with during transit. This security focus matters particularly when you’re publishing open-source packages to PyPI, as it protects against various attack vectors during the upload process. For private packages published to internal repositories, this same security ensures that your proprietary code is protected as it moves from your build system to your package index.

twine’s workflow is straightforward and intentionally minimal. After building your package with your chosen build system, whether that’s setuptools, hatchling, or another build backend, you run twine upload to publish to your target repository. The tool handles authentication, validates that your package meets basic requirements, and provides clear feedback if something goes wrong. This simplicity makes twine reliable for both manual releases where a human is running the upload command and automated CI/CD pipelines where the upload happens as part of your deployment process.

Here’s how you use twine in practice for both public and private package distribution:

# Install twine

pip install twine

# Build your package first (using setuptools, hatch, etc.)

python -m build

# Upload to PyPI

twine upload dist/*

# Upload to a private repository like RepoForge

twine upload --repository-url https://api.repoforge.io/your-hash/ dist/*

# Configure repository in ~/.pypirc for convenience

cat > ~/.pypirc << EOF

[distutils]

index-servers =

pypi

repoforge

[pypi]

username = __token__

password = pypi-your-token-here

[repoforge]

repository = https://api.repoforge.io/your-hash/

username = token

password = your-repoforge-token

EOF

# Now you can upload using the configured name

twine upload --repository repoforge dist/*

# Check your package before uploading to catch issues early

twine check dist/*

For organizations using private package repositories, twine is often the bridge between your build system and your package index, regardless of which build system you chose. Whether you’re building with setuptools, hatch, or poetry’s build command, twine provides a consistent interface for the upload step. The tool respects the standard .pypirc configuration file for storing repository credentials, making it easy to manage multiple deployment targets without embedding credentials in your scripts or CI configuration.

twine doesn’t try to do more than it needs to, and this focused approach makes it robust and reliable. It doesn’t build packages, manage dependencies, or handle environments. It simply uploads packages that you’ve already built to indexes that you specify. When you need to publish a package, twine does exactly what you expect without surprises or unnecessary complexity. This reliability is why twine remains the standard tool for package distribution even as other parts of the packaging ecosystem evolve and change.

hatch: The Modern, Standards-Based Alternative

hatch represents the newer generation of Python packaging tools with a focus on standards compliance and flexibility. Created by a PyPA member, hatch is designed around current Python packaging standards rather than creating proprietary formats or workflows. Like poetry, it provides an integrated experience for dependency management, environment management, building, and publishing, but it does so while maintaining compatibility with standard Python packaging conventions.

What makes hatch particularly interesting is its excellent support for managing multiple environments. You can define different environments for different Python versions, different dependency sets, or different purposes like testing, documentation, or development. For library maintainers who need to test against multiple Python versions and dependency combinations, this capability makes hatch especially valuable. The tool’s approach to versioning is also noteworthy, providing built-in version bumping and dynamic versioning from VCS tags, which streamlines release management. For projects that follow semantic versioning, hatch reduces the manual overhead of managing version numbers across releases.

PDM: Standards-Compliant Innovation

PDM takes yet another approach to Python packaging by positioning itself as a modern tool that strictly adheres to Python packaging standards while providing excellent performance. Like poetry and hatch, it generates lock files for reproducible environments, but it does so while maintaining close compatibility with packaging standards rather than introducing proprietary formats. This standards-focused approach means PDM projects are generally more interoperable with other tools and less likely to encounter compatibility issues with the broader ecosystem.

What makes PDM particularly interesting in 2026 is its hybrid capability. You can configure PDM to use uv as its installation backend by setting pdm config use_uv true, combining PDM’s flexible, standards-compliant CLI and plugin system with uv’s installation speed. This “hybrid” approach appeals to developers who want the best of both worlds—Pythonic configuration with Rust-based performance. The tool provides an interesting middle ground between the full integration of poetry and the focused approach of pip-tools, making it worth considering if you want modern features while ensuring your projects remain portable and standards-compliant.

Modern Python Packaging Standards: The Foundation of Interoperability

The chaos of “14 competing standards” from the XKCD comic has been substantially mitigated not by eliminating choices but by standardizing the interfaces between tools. In 2026, several key Python Enhancement Proposals (PEPs) have created a foundation of interoperability that allows different tools to coexist productively. Understanding these standards helps you appreciate why the modern ecosystem feels less fragmented than it did just a few years ago, even though more tools exist than ever before.

PEP 621: The Unifying Configuration Standard

PEP 621 standardizes how project metadata—name, version, dependencies, authors, and other critical information—is defined in pyproject.toml files. This standard is now supported by all major tools, which means you can define dependencies in standard TOML format and theoretically switch between uv, pdm, and hatch without rewriting your dependency lists. This interoperability represents a significant achievement for the Python Packaging Authority and has dramatically reduced the friction of moving between tools or maintaining projects that different team members work on with different tool preferences.

Here’s what a standard PEP 621 configuration looks like, compatible with uv, pdm, and hatch:

# A standard PEP 621 configuration

[project]

name = "enterprise-api"

version = "2.1.0"

description = "Core API service for data ingestion"

requires-python = ">=3.11"

authors = [

{ name = "Platform Engineering", email = "engineering@example.com" }

]

dependencies = [

"fastapi>=0.109.0",

"sqlalchemy[asyncio]>=2.0.0",

"pydantic-settings>=2.1.0"

]

[project.optional-dependencies]

dev = ["pytest>=7.0", "black>=23.0", "ruff>=0.1.0"]

docs = ["mkdocs>=1.5", "mkdocs-material>=9.0"]

[build-system]

requires = ["hatchling"]

build-backend = "hatchling.build"

The beauty of this standard is that it decouples your project’s metadata from your choice of tooling. Your project definition becomes portable, and you’re not locked into a particular tool’s ecosystem simply because you’ve committed to a configuration format.

PEP 723: Inline Script Metadata Revolution

One of the breakthrough features of 2026 is the widespread adoption of PEP 723, which allows dependencies to be declared directly inside a Python script using a specially formatted comment block. This solves an age-old problem in Python: sharing a single-file script that requires third-party packages. Previously, sharing such a script required also sending a requirements.txt file and providing instructions for creating a virtual environment. The recipient had to understand virtual environments, dependency management, and the relationship between the script and its requirements file.

With PEP 723, all of that complexity disappears. The script itself declares its requirements in its header, and tools like uv and pdm can read these declarations, provision an ephemeral environment with the specified dependencies, and execute the script automatically. This capability has largely replaced the need for pipx when running standalone scripts and has become particularly popular among DevOps engineers for writing portable automation scripts that can run anywhere without complex setup.

Here’s a practical example of a PEP 723 script that fetches data from an API:

#!/usr/bin/env -S uv run

# /// script

# requires-python = ">=3.11"

# dependencies = [

# "requests<3",

# "rich",

# "pandas",

# ]

# ///

import requests

from rich.pretty import pprint

import pandas as pd

def fetch_repoforge_stats():

"""Fetches statistics from the RepoForge API and displays them."""

try:

resp = requests.get("https://api.repoforge.io/stats")

resp.raise_for_status()

data = resp.json()

# Pretty print the raw data

pprint(data)

# Convert to DataFrame for analysis

df = pd.DataFrame(data.get('packages', []))

print(f"

Total packages: {len(df)}")

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error fetching data: {e}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

fetch_repoforge_stats()

To execute this script, you simply run uv run dashboard.py. The tool automatically provisions an ephemeral environment with requests, rich, and pandas cached from previous runs if available, and executes the script immediately. No pip install, no virtual environment activation, no requirements.txt to manage separately. The script is entirely self-contained and portable.

PEP 751: The Lock File Treaty

One of the most contentious aspects of Python packaging has been the “Lock File War.” For years, poetry used poetry.lock, PDM used pdm.lock, and pip-tools used requirements.txt for locking. There was no interoperability between these formats. A PDM project couldn’t be easily installed by poetry, and vice versa. Each tool’s lock file format was optimized for that tool’s specific needs and implementation details, creating genuine barriers to tool migration and team collaboration when different team members preferred different tools.

By 2026, PEP 751 has been accepted, attempting to create a unified lock file format called pylock.toml. The goal is to have a single file format that all installers can read, allowing for reproducible installs regardless of the tool used to generate the lock file. Think of it as a “lingua franca” for dependency locking that any tool can understand, similar to how PDF serves as a universal document format regardless of which application created the original document.

However, adoption in 2026 is mixed and worth understanding honestly. While the standard exists and is technically supported, major tools like uv and poetry still prefer their optimized, proprietary lock formats for day-to-day development. These formats can represent cross-platform wheels more efficiently, include tool-specific metadata that aids in faster resolution, and leverage implementation details that make installations faster. The tools generally treat PEP 751 as an export format—a way to generate a lock file for interoperability or auditing purposes—rather than a native core file format that drives daily development.

This creates a situation where the “standard” exists and provides value for specific use cases (auditing, security scanning, cross-tool compatibility checks) but functions more as a translation layer than as the primary lock file format most developers interact with. It’s progress toward unification, even if it’s not complete unification yet.

Feature Comparison: Understanding Tool Trade-offs

With multiple mature tools available in 2026, understanding their specific trade-offs helps you make informed decisions. The following table provides a comprehensive comparison of the major packaging tools across key features:

| Feature | uv | poetry | PDM | hatch | pip |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Rust | Python | Python | Python | Python |

| Primary Philosophy | Performance & Unification | Determinism & UX | Standards & Flexibility | Environments & Building | Foundation & Compatibility |

| Python Version Management | Native (downloads & installs) | Limited (via plugins/pyenv) | Limited (via plugins) | Limited (via plugins) | No |

| Lock File Format | uv.lock (universal cross-platform) | poetry.lock | pdm.lock | No default lock* | No (use pip-tools) |

| Build Backend | Uses external (defaults to hatchling or setuptools) | poetry-core | pdm-backend | hatchling | N/A (uses setuptools or others) |

| PEP 621 Support | Native | Native | Native | Native | N/A |

| PEP 723 Support | Native | No | Yes | No | No |

| Monorepo Support | Native (Workspaces) | Plugin required | Limited | Native (environment inheritance) | No |

| Dependency Resolution | Parallel, highly optimized (PubGrub variant) | Serial, rigorous (PubGrub) | Serial, compliant | Delegates to pip/uv | Serial, reference implementation |

| Installation Speed | Fastest (10-100x) | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate (depends on backend) | Baseline |

| Plugin Ecosystem | Limited (new) | Mature | Growing | Growing | Extensive |

| Best For | Applications, monorepos, speed-critical workflows | Libraries, complex dep trees, mature projects | Standards compliance, hybrid workflows | Library maintenance, testing matrices | Universal compatibility, education |

*hatch generally focuses on environment matrices rather than application locking, though extensions exist.

This table highlights that no single tool is universally “best.” Rather, each tool excels in different scenarios. uv dominates in speed and unified workflows. poetry excels in deterministic resolution for complex dependency graphs. PDM shines in standards compliance. hatch is unmatched for environment matrices and testing. pip remains the universal foundation that everything builds upon.

Monorepos and Workspaces: The New Architecture of Scale

As Python applications in 2026 grow larger and organizations adopt more sophisticated development practices, the traditional “one repository per package” model has largely been supplanted by monorepos. Large organizations increasingly place multiple related services, libraries, and tools into a single Git repository for reasons ranging from atomic cross-project changes to simplified dependency management to better code sharing. Managing multiple interdependent Python packages in a single repository was historically painful, involving complex PYTHONPATH hacks, script-heavy CI pipelines, and constant version synchronization headaches.

uv and poetry have both introduced specific features to address monorepo challenges, fundamentally changing how large-scale Python is architected. Understanding these capabilities helps you decide whether monorepo architecture makes sense for your organization and which tool best supports that architecture if you adopt it.

uv Workspaces: Unified Lock Files for Consistency

Borrowing concepts from Rust’s Cargo workspaces, uv introduced native workspace support that has become the gold standard for Python monorepos in 2026. The key innovation is the unified lock file. Instead of each package in your monorepo maintaining its own lock file that might drift out of sync with others, uv creates a single lock file at the repository root that covers all packages simultaneously.

Here’s what a typical uv workspace structure looks like:

/my-monorepo

├── pyproject.toml # Workspace root configuration

├── uv.lock # Single unified lockfile for entire repo

├── packages/

│ ├── core-lib/

│ │ └── pyproject.toml # Package-specific configuration

│ ├── api-service/

│ │ └── pyproject.toml # Depends on core-lib

│ └── worker-service/

│ └── pyproject.toml # Depends on core-lib

The root pyproject.toml defines the workspace members:

# /my-monorepo/pyproject.toml

[tool.uv.workspace]

members = ["packages/*"]

[project]

name = "my-monorepo"

requires-python = ">=3.12"

Why this matters: When a developer runs uv sync at the repository root, uv resolves dependencies for all packages simultaneously. It ensures that if core-lib uses pydantic==2.8.0, both api-service and worker-service also use that exact version. This guarantees consistency across your entire fleet of services and eliminates “diamond dependency” issues between internal components where different services depend on conflicting versions of shared dependencies.

The unified lock file approach means that when you update a dependency in one package, uv re-resolves the entire dependency graph to ensure nothing breaks anywhere in the monorepo. This prevents the subtle bugs that occur when different services test against different dependency versions locally but get deployed with different versions in production. It allows for “editable” installs of internal packages by default, so changes in core-lib are immediately reflected in api-service without re-installation or build steps.

CI/CD Strategies for Monorepos

Monorepos introduce complexity in CI/CD pipelines. If one package changes, you typically don’t want to rebuild and redeploy everything—that would negate many of the efficiency benefits of the monorepo structure. You need selective building and testing based on what actually changed.

uv supports intelligent caching and selective operations that make this practical:

# Example CI workflow for a monorepo

# 1. Sync the environment (uses cached wheels if lockfile hasn't changed)

# The --frozen flag ensures no resolution happens, only installation

uv sync --frozen

# 2. Run tests only for the 'api-service' package

# This runs only the tests for the specific package that changed

uv run --package api-service pytest

# 3. Build only changed packages

# You can use git diff to determine which packages need rebuilding

uv build --package api-service

Tools like RepoForge.io play a crucial role in monorepo CI performance by serving as the central cache for built wheels of internal packages. If core-lib hasn’t changed between builds, the CI pipeline pulls the pre-built wheel from your private repository cache rather than rebuilding it from source. This can save significant compute time, especially for packages with C extensions or complex build processes. The combination of uv’s workspace support, intelligent caching, and a fast private repository creates CI pipelines that remain fast even as monorepos grow to dozens of internal packages.

Comparison with poetry Monorepo Support

poetry supports similar monorepo functionality but relies on “path dependencies” and external plugins like poetry-plugin-monorepo or poetry-monoranger-plugin to achieve true workspace behavior. The approach works but often requires separate lock files for each sub-project unless you use specific plugins, which can lead to version drift between services in the same repository.

# poetry approach to monorepo dependencies

[tool.poetry.dependencies]

python = "^3.11"

my-core-lib = { path = "../core-lib", develop = true }

While functional, the poetry approach in 2026 is generally viewed as less cohesive than uv’s native implementation for monorepo scenarios. The plugin ecosystem is mature and can handle complex cases, but it requires more configuration and manual synchronization. For organizations specifically optimizing for monorepo architecture, uv’s unified lock file approach is generally considered superior for maintaining rigorous consistency.

Choosing Your Tools: Practical Recommendations

With so many options available, choosing the right combination of tools can feel overwhelming. However, the decision becomes clearer when you consider your specific circumstances, your team’s experience level, your project’s requirements, and your organization’s constraints. Rather than looking for a single perfect tool that does everything, think about which combination of specialized tools will give you the best outcomes for your particular situation.

For new Python projects, especially applications like web services, data pipelines, or internal tools, starting with poetry or hatch provides immediate value. These tools offer integrated workflows that handle dependency management, environment management, and package building through a single interface. poetry has the larger community and more mature ecosystem at this point, with extensive documentation and widespread adoption that means you’ll find answers to common questions easily. hatch offers more flexibility and closer adherence to standards, which can matter if you need to integrate with existing tooling or want to avoid potential lock-in to tool-specific approaches. Either choice will serve you well for most application development scenarios, and the decision often comes down to which tool’s philosophy resonates more with your team.

For existing projects where you already have established workflows and infrastructure, the migration path matters enormously. Completely rewriting your build and deployment processes to adopt a new integrated tool creates risk and consumes time that might be better spent on features or other improvements. If you’re currently using requirements.txt files and pip, adopting pip-tools to add lock file functionality represents the lowest-friction upgrade path. You keep your existing workflows intact, your deployment scripts continue working unchanged, and your team doesn’t need to learn an entirely new tool ecosystem. You simply add one compilation step that generates pinned requirements from your input requirements, gaining reproducibility without disruption. Once you’re comfortable with lock files and see the value they provide, you can evaluate whether moving to a more integrated tool makes sense for your situation, but you’re not forced to make that leap all at once.

For large organizations with complex requirements that span multiple teams, multiple projects, and multiple deployment environments, using different tools for different purposes often produces the best results. You might use pip-compile for lock file generation because it integrates seamlessly with your existing deployment pipeline and provides the flexibility you need for managing different environment types. You might use uv for fast package installation in CI where speed directly translates to infrastructure cost savings. You might use twine for publishing to your private repository because it provides secure, reliable uploads that work consistently across different package types. This mix-and-match approach lets you optimize each part of your workflow independently, and it prevents you from being blocked by a single tool’s limitations in one area affecting your entire stack.

For library development, where you’re creating packages that other developers will depend on, the considerations shift somewhat. You need excellent support for building distributable packages, managing version numbers across releases, and testing against multiple Python versions and dependency combinations. hatch excels in this role with its environment management capabilities that make testing against different configurations straightforward. poetry also works well for library development, though its opinions about project structure can sometimes feel constraining. Many library maintainers still use setuptools directly with pip-tools for dependency management, finding this combination flexible enough to handle their specific needs while remaining simple and transparent. The choice often depends on how much you value integrated features versus maximum flexibility and control.

If your team values speed above almost everything else and you have relatively straightforward requirements without unusual edge cases, replacing pip with uv everywhere can yield immediate benefits. The installation speed improvements are real and significant, particularly for projects with many dependencies or teams that create and destroy environments frequently. However, remember the CI caveat we discussed earlier. If your CI runs on minimal virtual machines with limited CPU allocation, uv’s advantage diminishes because its parallelism can’t fully exploit single-core environments. In these cases, the combination of uv with a fast private repository like RepoForge addresses both bottlenecks, giving you back the dramatic improvements even in constrained environments.

For organizations handling sensitive code or operating in regulated industries with compliance requirements, private package repositories aren’t optional. They’re essential infrastructure that provides security, control, and auditability. Every package that reaches your developers passes through your repository first, where you can scan it, approve it, and ensure it meets your standards. When deciding on tooling, ensure your chosen tools integrate cleanly with private repositories. All the major tools we’ve discussed support custom package indexes, but the ease of that integration varies. pip-tools and uv make it trivial because they’re built on pip’s foundation. poetry requires configuration but works well once set up. The key is ensuring your tooling supports your security requirements without creating friction that developers will want to work around.

Best Practices for Python Packaging in 2026

Regardless of which specific tools you choose for your Python packaging workflow, certain practices remain universally valuable and provide benefits that compound over time. These practices represent lessons learned from years of production Python development across organizations of all sizes, and adopting them early in your project’s lifecycle pays dividends throughout its lifetime.

Always use lock files or equivalent mechanisms to ensure reproducible environments. The difference between “it works on my machine” and “it works everywhere” often comes down to dependency version mismatches that lock files prevent. When you commit a lock file to version control, you’re guaranteeing that everyone on your team, your CI system, and your production deployment all use identical dependency versions. This eliminates an entire class of bugs where code fails in production because production happened to resolve a dependency differently than development did. Whether you use poetry’s poetry.lock, pip-compile’s requirements.txt, or another tool’s lock file format, the key is committing those lock files and ensuring they’re actually used during installation.

Pin your dependencies tightly in production but stay relatively looser in development, though this might seem contradictory at first glance. In production, you want absolute stability and reproducibility. You want the exact same code running every time you deploy, which means the exact same dependency versions. Your lock files provide this guarantee. In development, however, you want to catch issues with new dependency versions relatively early, before they become production problems. Your lock files should still pin versions to ensure consistency across your team, but you should regularly update those lock files to pull in newer versions and test them in your development and staging environments. This practice helps you discover breaking changes or new bugs in dependencies before they impact production, while still maintaining reproducibility when you need it.

Separate your direct dependencies from your transitive dependencies in your thinking and in your tooling configuration. Your direct dependencies are the packages you explicitly chose to use because they provide functionality your code needs. Your transitive dependencies are what those packages depend on, which you use indirectly through your direct dependencies. Tools that maintain this separation, like pip-compile with its .in and .txt files or poetry with its distinction between dependencies and lock file contents, make it easier to understand and manage your dependency graph. When a security vulnerability is discovered in a transitive dependency, this separation helps you trace which direct dependency pulled it in and whether you can update or replace that direct dependency to get a safe version of the transitive one.

Use private package repositories for any code that’s internal to your organization, even if you’re a small team. The temptation to use git dependencies, vendor code directly into your repositories, or publish internal code to public PyPI with obscure names creates problems that multiply as your projects grow. Private repositories like RepoForge.io make internal package distribution so straightforward that there’s little reason not to establish this pattern from the beginning. Your internal packages are installed the same way as public ones, using the same tools and workflows, which reduces cognitive load and makes onboarding new team members simpler. The security benefits we discussed earlier matter just as much for small teams as for large organizations.

Invest in fast CI/CD pipelines from the start rather than treating slow builds as an inevitable annoyance. The speed of your packaging tools directly impacts your deployment frequency, your ability to quickly roll back bad changes, and your developers’ productivity when they’re waiting for tests to complete before merging pull requests. Tools like uv can cut CI times significantly, but remember to address both bottlenecks: CPU utilization through parallel operations and network latency through fast package indexes. Using uv with a low-latency private repository gives you multiplicative improvements rather than just additive ones. When you’re running hundreds or thousands of builds per day, these improvements translate directly to infrastructure cost savings and faster iteration cycles.

Document your tooling choices and the reasoning behind them for your team and future maintainers. Python packaging can be confusing, especially for developers new to Python or new to your organization. When someone joins your team and wonders why you use pip-compile instead of poetry, or why you have a private repository, or why your CI uses uv instead of pip, having documentation that explains the trade-offs you considered and the benefits you’re getting makes their onboarding smoother and reduces the likelihood that they’ll propose changes that undo valuable patterns you’ve established. Your documentation should include setup instructions that actually work, common workflows that developers need daily, and troubleshooting tips for your specific tool combination. Keep this documentation in your repositories where it’s versioned alongside your code and can evolve as your practices evolve.

Regularly audit your dependencies for security vulnerabilities and license compliance issues. Tools like Safety for security scanning and pip-licenses for license checking should run automatically in your CI pipeline, failing builds if they detect problems. Don’t wait for a security incident to start thinking about dependency hygiene. When you use a private repository, you can implement these checks at the repository level, scanning packages as they’re published and blocking problematic packages before they reach any developers or make it into any builds. This proactive approach is far superior to reactive security patching after vulnerabilities are discovered in production.

Looking Forward: The Future of Python Packaging

The Python packaging ecosystem in 2026 is healthier and more capable than it has ever been, but it’s certainly not finished evolving. Understanding where the ecosystem is heading helps you make tooling decisions that will age well and positions you to take advantage of new capabilities as they emerge. Several clear trends are shaping the next evolution of Python packaging, and being aware of these trends informs the choices you make today.

The Rust Revolution Continues

The trend toward Rust-based tooling shows no signs of slowing down and may actually be accelerating. We’ve seen this with uv bringing dramatic speed improvements to package installation, and with ruff revolutionizing Python linting and formatting. The performance characteristics of compiled Rust code, combined with Rust’s memory safety guarantees, make it an attractive choice for building the next generation of Python tooling. Expect to see more Python tools rewritten in Rust for performance over the coming years, potentially including build systems, test runners, and other parts of the development workflow. This doesn’t mean Python-based tools are going away or becoming obsolete. Many excellent tools remain Python-based and work perfectly well for their intended purposes. However, the performance bar is rising, and developers are beginning to expect that their tools should be fast enough to stay out of the way rather than being bottlenecks that interrupt flow.

Standards Convergence and Interoperability